By Abdulmesih BarAbraham

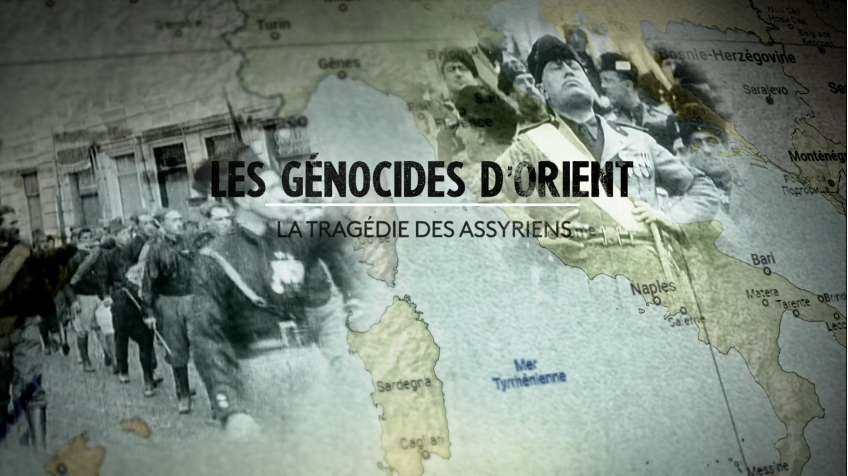

A documentary film on the Assyrian Genocide (also known as Sayfo, “the sword”),

released resently in France, highlights the Assyrian tragedy during World War I. It is

entitled LES GENOCIDES D’ORIENT: LA TRAGÉDIE DES ASSYRIENS

[Genocide in the Orient: The Tragedy of the Assyrians].

In the documentary, renowned professors, historians and genocide scholars, explain the

background and the unfolding of the events that led to the destruction of half of the

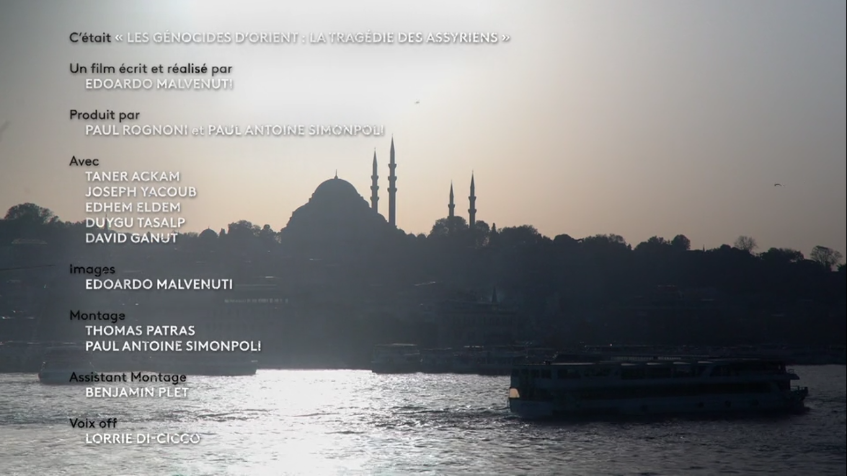

Assyrian population in the Ottoman Empire. The film was written and directed by

Edoardo Malvenuti while realized by Paul Rognoni Paul Antonie Simonpoll.

Introduction: Reclaiming a Silenced Past

Genocide in the Orient: The Tragedy of the Assyrians confronts one of the most

obscured and repressed chapters in the history of the First World War — the

extermination of Christian minorities within the late Ottoman Empire, with a particular

focus on the Assyro-Chaldeans. Through archival imagery, haunting landscapes, and

the commentary of five distinguished historians — Taner Akçam, Joseph Yacoub,

Edhem Eldem, Duygu Tasalp, and David Gaunt — the film reconstructs a forgotten

genocide and exposes the enduring silence that surrounds it in modern Turkey.

While the Armenian genocide has gradually entered international consciousness, the

suffering of the Assyrians has long remained marginal in historical and political

discourse. The documentary situates this tragedy within the broader context of the

Ottoman Empire’s collapse, nationalist radicalization, and the logic of ethnic

homogenization that defined the emergence of modern Turkey.

The Ottoman Empire in Decline: From Multinational State to Ethnic Nationalism

The film opens in the ancient Assyrian Christian heartland of Tur Abdin, southeastern

Anatolia — a landscape marked by monastic ruins and silence. These vestiges, the

narrator tells us, are not merely relics of faith but of destruction and painful memory.

Taner Akçam situates the origins of the genocide not in 1915, but earlier — in the

Balkan Wars (1912–1913). He explains that the.

Ottoman Empire’s loss of nearly all its European territories and much of its Christian population

constituted “a deep trauma” for the ruling elites. From this moment, he argues, “the Ottoman

government understood there was no possibility to live side by side with Christians.”

Joseph Yacoub adds that after the Balkan defeat,

non-Turkish and non-Muslim communities were perceived as existential threats to Anatolia’s

integrity — a perception that laid the ideological foundation for later acts of extermination.

By 1913, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) — a nationalist revolutionary movement — seized power through a coup, forming a dictatorial triumvirate under Talaat, Enver, and Djemal Pasha.

As historian Edhem Eldem observes, Ottoman politics thereafter “shifted toward

fascism, dictatorship, and militarism,” merging Islam with the language of security and

national survival.

Duygu Tasalp reinforces this point: for the Unionists, nationhood was “built upon

Islam,” and the Muslim “dominant.

nation” was thus entitled — even obliged — to subjugate or eliminate

the non-Muslim others.

World War I: The Context for

Extermination

When World War I broke out, the Ottoman Empire entered on the side of Germany.

The Eastern Front — along the border with Russia — became a crucible of paranoia

and suspicion. Akçam notes that Armenian volunteers joined the Russian army, an act

that Ottoman authorities interpreted as a betrayal. This perception extended to other

Christian groups, including the Assyrians, whose communities straddled the frontier.

As David Gaunt explains, the Assyrians’ limited contact with the Russians — driven

by desperation and survival — was used by the Ottoman state as justification for

collective punishment: “They had no alternative… but the Turks knew about this. They

had intercepted messages.”

Thus began the logic of preemptive annihilation. In 1914–1915, the Ottoman authorities targeted

Assyrian villages in the Hakkari region. Joseph Yacoub recounts how Kurdish tribes, armed and

encouraged by the state, spearheaded attacks that decimated the Assyro-Chaldean population. “This was the spark,” he says, “that truly ignited the region.” Half the Assyrian population perished through massacre, starvation, or forced marches.

The Machinery of Genocide

By spring 1915, as Ottoman forces suffered defeat in the Caucasus, the CUP resolved

upon what Taner Akçam calls the “final decision to exterminate the Armenians and

remove the entire population from Anatolia.” Although the Assyrians were not initially

designated as a central target, Akçam explains that local authorities implemented

parallel deportations, erasing the distinction between Armenian and Assyrian

Christians.

Duygu Tasalp highlights the bureaucratic coordination of this process: daily telegrams

flowed between the Interior and War Ministries, detailing deportations and property

confiscations. Eldem adds that war conditions enabled “organized extermination,” with

military mobilization and the pretext of treason justifying atrocities. Kurdish militias,

backed by the CUP, became instruments of terror across eastern Anatolia.

One of the epicenters was Diyarbakir, governed by Rechid Bey, who organized mass

killings with impunity. Tasalp’s stark testimony enumerates the methods of destruction

— women and children thrown into wells, ravines, and rivers, “archaic” yet profoundly

dehumanizing techniques that prefigured the logic of later genocides.

Despite moments of resistance — most notably the siege of Ainwardo, where hundreds

of Assyrians resisted for nearly two months — the outcome was annihilation. Survivors

were driven south into the Syrian desert, where starvation completed the genocidal

plan.

As Tasalp underscores, deportation itself was conceived as extermination: Ottoman

parliamentary records show that leaders knew deportees would not survive. David

Gaunt grimly quantifies this policy: “20 percent survived, 80 percent died on the way.”

Aftermath and Denial: From Empire to Republic

The war ended in 1918, leaving Anatolia devastated and largely emptied of its Christian

populations. The triumvirs fled to Germany, and for a brief moment, postwar tribunals

attempted to hold perpetrators accountable. Akçam recounts that Allied occupation of

Istanbul compelled Ottoman authorities to stage trials (1919–1920), and Duygu Tasalp

notes that several CUP officials were indeed condemned. Yet, as Gaunt points out,

public backlash was fierce: “Reshid Bey… committed suicide… others were sent to

Malta,” effectively ending the judicial process.

At the Paris Peace Conference (1919), Joseph Yacoub reminds us, Assyro-Chaldean

delegates sought recognition and a national homeland, but their pleas “were not heard by the great powers.” Their tragedy was overshadowed by geopolitical interests — the

drawing of new borders across the Middle East.

Tasalp describes how remnants of the CUP regrouped in Anatolia under Mustafa

Kemal (Atatürk) and how these same figures “formed the political personnel of the new

Republic of Turkey.” The Kemalist revolution thus institutionalized a profound

historical silence: the Republic’s birth coincided with the erasure of its Christian

victims. “Turkey,” she asserts, “was born out of genocide… The taboo lies in the fact

that we exist because they no longer exist.”

Akçam identifies two enduring reasons for denial: political continuity (the same cadres

that organized the genocide founded the Republic) and fear of reparations. Admitting

guilt, he explains, would mean acknowledging responsibility and potential

compensation claims. Eldem expands this argument to a global level, suggesting that

the great powers themselves preferred to “sweep this story under the rug” — a tacit

complicity born of political convenience.

Memory and Recognition

The film closes by tracing the slow re-emergence of memory. Whereas the Armenian

diaspora long preserved its history through activism and testimony, the Assyrian

Genocide remained nearly invisible until the 21st century. Duygu Tasalp notes that

2015, the centenary of the genocide, marked a turning point: new voices in Turkey,

Europe, and beyond began calling for recognition. Even Pope Francis publicly named

the Armenian, Assyrian, and Greek massacres as “the first genocide of the 20th

century.”

Yet, Tasalp concludes, Turkey “missed this opportunity” to face its past — moving

instead toward renewed authoritarianism and isolation. The film’s final images linger

over the empty monasteries of Tur Abdin, their silence speaking louder than denial

itself.

Conclusion: Confronting the Void

Genocide in the Orient: The Tragedy of the Assyrians is both historical reconstruction

and moral meditation. By giving voice to historians from Turkey, France, and Sweden,

it dismantles the nationalist myth of a “homogeneous Anatolia” and restores the

Assyrians to the tragic map of the 20th century.

The strength of the film lies in its chronological clarity and intellectual integrity: each

scholar connects historical facts to moral consequences, revealing a continuum from

imperial collapse to state denial. The documentary’s ultimate message is not only about

what was destroyed but about what remains—the silence, the ruins, and the fragile

work of remembrance.

Video:

https://vimeo.com/1092757727/9788ead861?ts=0&share=copy

Note: All images are screenshots.