AN INTERVIEW WITH AHMET KARDAM, THE GRANDSON OF BEDIRKHAN BEY

// Sabri Atman –

The Assyrians’ homeland is Mesopotamia between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Their history in this geography goes back thousands of years. Due to the divisions in the history of the Church, they were known by many different names. Nestorians are one of them! At the Council of Ephesus in 431 A.D., due to theological disagreements, some rejected Nestor’s views on the nature of Jesus and set a new path for their followers. Those who accepted these ideas were called Nestorians. In short, Nestorianism is the name given to the different paths taken by people of the exact ethnic origin who believe in various interpretations of Christianity. They are also called the Eastern and Western Churches.

During the 19th century, Nestorians lived in the border regions of Iran-Urmia and Ottoman lands. Most of the Nestorians residing in these two regions lived as tribes between Van and Hakkâri in Ottoman territory and also made a living from agriculture and animal husbandry. There are different figures regarding the population in this region. Some pronounce the figure of seventy-five thousand, and some give the figure of one hundred and fifty thousand.

The year must have been 2007. Hrmis Aboona, the author of several books such as “Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans,” and I were invited by the Firodil Institute for a conference in London. Aboona was to focus on the Nestorian massacres of 1843 and 1846; I was to focus on the genocide of 1915. Aboona emphasized two issues. First, the lack of Assyrian national consciousness and the rule of the people by tribes was a major problem. They were unable to act together against attacks from outside. Secondly, the massacre of tens of thousands of Assyrians and the lack of accountability for these massacres laid the groundwork for the 1915 genocide. As a result, the local Nestorian population in the Hakkâri region was utterly wiped out. The demography was completely changed. The Nestorians had lost not only tens of thousands of their people but also their property and land. Those who survived were forced to migrate to other lands. Frankly speaking, the perpetrators of the massacre were the winners.

The survivors sought a new life in Urmia and other regions of Iran after Talat Pasha ordered their deportation with a decree sent to the governor of Van in October 1914. In response to their desire to return, he sent a telegram to the governor of Mosul on October 30, 1915, ordering them not to return to their homeland.

Continuing Talat Pasha’s policy of Turkification, Mustafa Kemal Pasha, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, finalized the ethnic cleansing by not allowing the Nestorians to return to their homeland. Hakkâri was home to tens of thousands of Assyrians, but today it is devoid of its natives. Only traces of some church ruins can be found there. The children of the survivors live in Arizona in the United States, Chicago, Australia, and Canada.

In 2013, Petros Gwargis, a man I met in Saint Petersburg, Russia, whose ancestors were from Hakkari, told me that his greatest longing was to follow in his ancestors’ footsteps and visit Hakkâri before he died. He had been to Turkey twice for this purpose, but each time he had been told that it was not safe to go to Hakkâri. Weeks ago, I sent him a message, telling him that I was friends with Ahmet Kardam, the grandson of Badrkhan Bey, and that I had interviewed him about his grandfather’s massacres of the Nestorians. Petros Gwargis’ questions continued unabated. His first question was, “Does he think like his grandfather?” No, Ahmet Kardam said that the massacres were genocide and that they should “never happen,” and when I told him that he was calling on the Kurds to confront the genocide, he rejoiced like a child. He kept asking whether he could go to Hakkari, whether the Kurds would see him as an enemy, and whether anything would happen if he went there with his children.

I wish this interview with Ahmet Kardam will at least lead to a constructive dialogue between Assyrians and Kurds and contribute to a discussion in this direction.

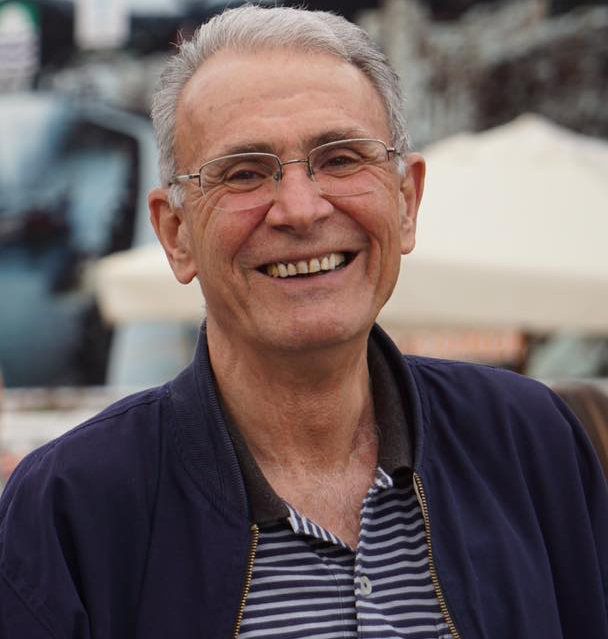

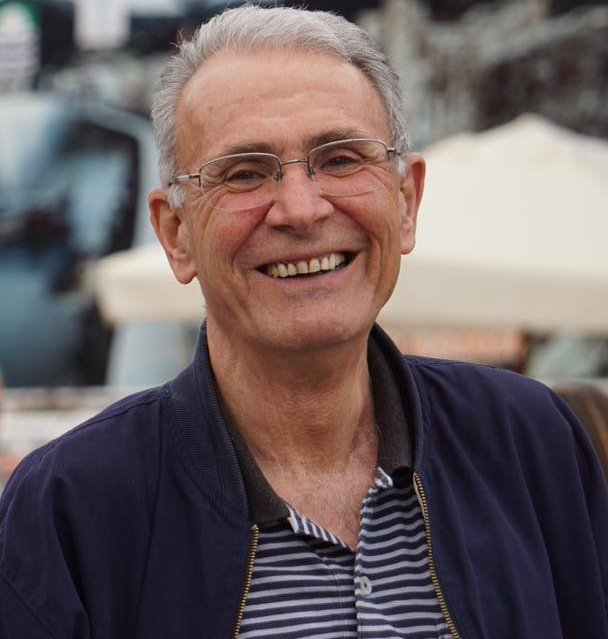

Could you please introduce yourself to our readers?

Born in Istanbul in 1945, I completed my primary school education in Ankara and my secondary and high school education at Tarsus American College. In 1964, I became a Middle East Technical University (METU) student. In 1969, I graduated from the Economics Department of the Faculty of Administrative Sciences of the university and started working as an economics assistant in the same department. As a result of the March 12, 1971 military coup, I was forced to leave my position at the university and become a political asylum seeker in the Netherlands. When a general amnesty was declared in the fall of 1974, I returned to Turkey. I worked as a translator and editor for various publishing houses. In 1976, my work on the Republican People’s Party was published as a book. In 1980, I started as deputy editor-in-chief of the Istanbul Daily Politika. Following the September 12, 1980, military coup, I was wanted by the police and had to go to Federal Germany as a political asylum seeker. I worked as editor-in-chief and columnist for Türkiye Postasi in West Berlin. I returned to Turkey in the fall of 1989, was detained by the police at the airport, and was imprisoned for a year and a half until April 1991. Between 1993 and 1998, I worked as the director of a public opinion research company’s Ankara office and IT center. A study I wrote with a friend titled Political Polarization and Voter Behavior in Turkey was published in 1998. Between 1999 and 2008, I worked as a translator and writer for a publishing house. The book I wrote about the famous Sufi Mevlana was published in 2007. I retired in 2008. My five-year study on the documents related to Bedirkhan Bey in the Ottoman archives was published in two volumes (2011 and 2013). My four-year study on Mustafa Suphi, the founder and first president of the Communist Party of Turkey, was published in 2020. My wife and I have been living in Foça, Izmir, since 2014. We have a son and two grandchildren living in Berlin.

When and how did your sensitivity to social events begin? Would you like to talk about your political struggle?

My sensitivity to social events started as a student at the Middle East Technical University in Ankara. I entered the university in the fall of 1964. The second half of the 1960s was when youth movements were on the rise in major countries worldwide. It was the same in Turkey. In Turkey, where socialist and communist views and activities had been severely punished for many years, a brand-new atmosphere began to blow in Turkish political life when a group of workers, taking advantage of the environment of freedom created by the relatively liberal constitution adopted in 1960, founded a party called the Workers’ Party of Turkey and opened its doors to progressive, democratic and socialist intellectuals. The 15 deputies that this party succeeded in getting into the parliament in the 1965 general elections formed an amazingly effective opposition focus. The trade union struggle of workers began to rise, socialist and communist ideas became widespread, and in parallel with these developments, a youth movement emerged in the universities, which grew stronger and more widespread. The Middle East Technical University, where I studied, housed an essential part of the youth movement that was on the rise. This general atmosphere in Turkey and the socialist student organization at the university where I was a student also affected me in 1966. I joined the university’s Socialist Ideas Club. In the elections for the Student Union executive board held in 1967 at the university, which had around five thousand students, the list I was a candidate for won. Hence, when the youth movement was at its peak in Turkey, I assumed responsibility for one of the essential organs of the youth movement.

In the fall of 1967, when the Cyprus problem flared up again, then US President Lyndon Johnson sent Cyrus Vance to Turkey on November 22, 1967 to mediate between Turkey and Greece. To protest the US intervention in the Cyprus problem, the METU Student Union took a large group of university students by bus to the airport where Vance’s plane was to land, occupied the airport, and then went to the United States Information Service (USIS) in the city center to stage a large protest. The police had attacked the demonstrators and detained some of them. I was detained, and the court sentenced me to nine months in prison on charges that I was among the demonstration organizers. This decision was finalized only four years later, in the spring of 1971. At that time, I had graduated from METU and worked as an economics department assistant. Around that time, on March 12, 1971, a military coup took place, and the army took over the country. Under these circumstances, the university administration immediately terminated my assistantship. I was imprisoned in a small town in Anatolia to serve my nine-month sentence. When my sentence was completed, the Ankara Martial Law Command ordered me not to be released but to be sent to Ankara. I was put in a military prison in Ankara. The military court on duty made the mistake of releasing me by ruling that I should be tried without arrest. This gave me the opportunity to escape to the Netherlands using a real passport obtained by a fake identity card. I was sentenced to ten years imprisonment by the military court that tried me in absentia.

During my exile in the Netherlands, I was among the founders of an organization that would defend the rights of migrant workers from Turkey. 50 years after its foundation, this workers’ union continues its work today as a mass organization respected by the official institutions of the Netherlands.

In 1974, I returned to Turkey, taking advantage of the amnesty law enacted at the end of the military regime. I became a member of the Communist Party of Turkey, which had been forced to carry out its activities illegally since its foundation in 1920. I published the documents of the party’s illegal conference in 1977 and ensured they were legally distributed and sold. I was immediately charged with “making propaganda for communism”. While I was on trial, on September 12, 1981, the army staged a coup d’état and seized control of the country, and police persecution of all opposition circles began. The police were after both me and my wife. We fled to Berlin with false passports provided by the party and applied for political asylum. The trial against me continued. I was sentenced to 7.5 years in absentia.

I, my wife, and son settled in West Berlin. In 1985, I became the secretary of the West Berlin organization of the Communist Party of Turkey, which was active among migrant workers from Turkey. Soon after, I became a member of the entire Western European committee. In the fall of that year, in a joint press conference held in Brussels, the Secretary General of the Communist Party of Turkey and the Chairman of the Workers’ Party of Turkey announced that the two parties had decided to unite under the name of the United Communist Party of Turkey, that this party would take its final form at a congress in 1988, and that the aim was to legalize this party by breaking the ban on communist parties. Shortly afterward, in November 1987, the general secretaries of the two parties returned to Turkey to lift the ban on the Communist Party and legally establish the United Communist Party of Turkey. They were immediately detained at the Ankara airport, where they landed, and after a heavy interrogation and torture, they were arrested and put on trial. A widespread and powerful solidarity movement arose both in Turkey and in Europe for the release of the two communist general secretaries and the lifting of the ban on the Communist Party.

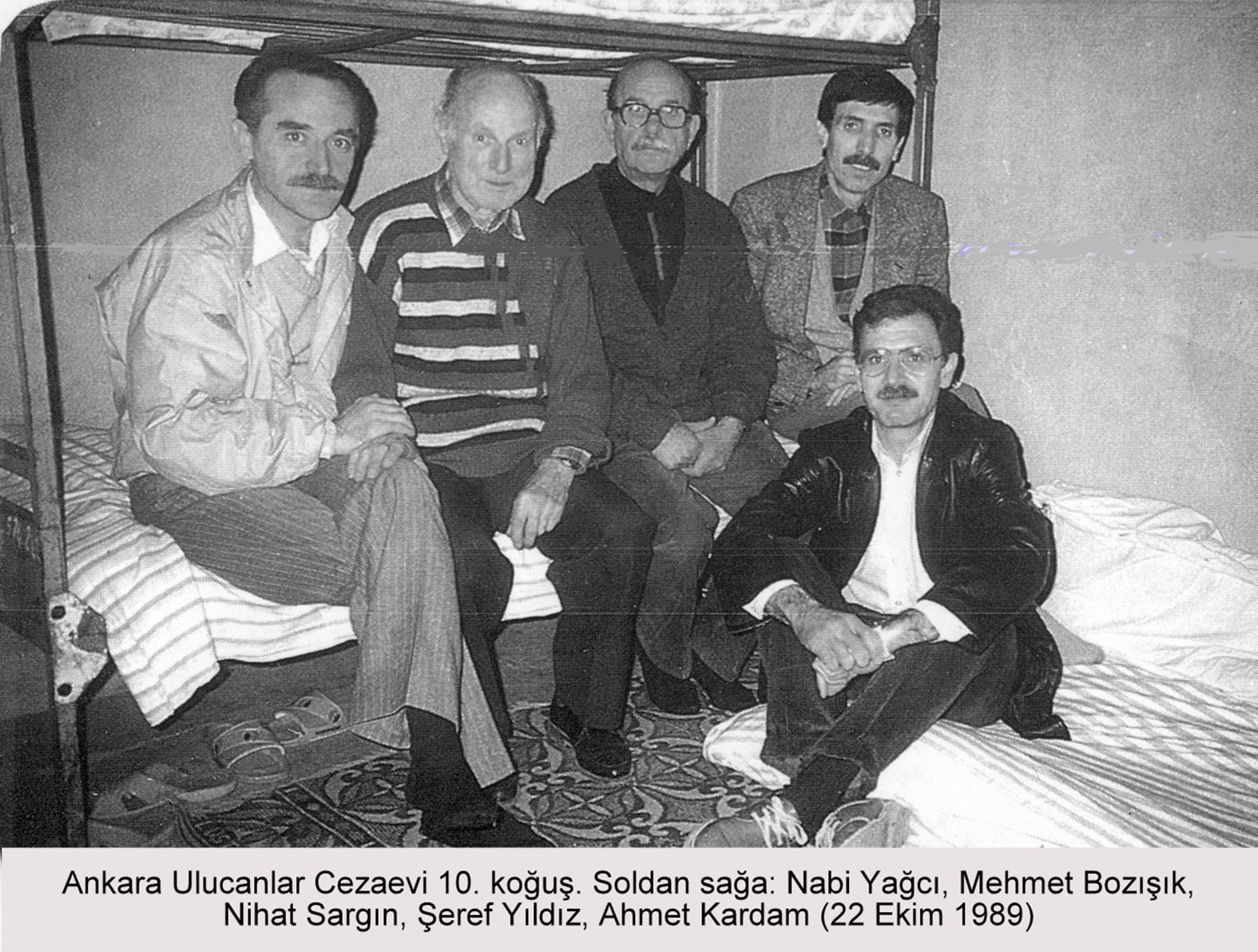

In the fall of 1989, to intensify the struggle for legality, a delegation of four members of the Central Committee, including myself, returned to Turkey. We were immediately taken into custody and arrested as soon as we landed at the airport. This second “repatriation movement” also aroused considerable resonance both at home and abroad. The first achievement in the struggle for legalization was the release of two general secretaries who had started a hunger strike. Although a release order was also issued for me, I was not released because of the previous 7.5-year heavy prison sentence against me.

The “struggle for legality” we had started achieved its goal when the Turkish regime was forced to lift the 70-year ban on the communist party in April 1991. Thus, I also regained my freedom.

The United Communist Party of Turkey, which had finally realized its legal establishment at its first legal congress, invited its members to join the newly established Socialist Unity Party to unite with other socialists and communists and thus ended its activities. Although I supported this decision taken by congress, I withdrew from active political life.

Although Anatolia is a geography with many ethnic identities, with the establishment of the Republic of Turkey, everything is being homogenized. Everyone is forced to say that they are happy ‘being Turkish’. What is your ethnic identity? Are you ‘happy’ to be Turkish?

The homogenization and Turkification of the multi-ethnic, multi-national Anatolian lands began before the establishment of the republic (1923). The leadership of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which had seized power in the last period of Ottoman rule, saw in Turkism the only way to prevent the empire’s disintegration. As a result of the great territorial losses suffered with the loss of the Balkan Wars, the leadership of the CUP felt that Asia Minor (Anatolia), with the Muslim population coming from the Caucasus and the Balkans, had to be turned into a “Turkish homeland”, the last piece of land where Turkishness could find refuge. But the demographic structure of Asia Minor was problematic. The number of Greeks, Armenians, Kurds, and Assyrians living in these lands amounted to millions; Turks were in the minority. Therefore, CUP aimed to homogenize the demographic structure by cleansing it. For this purpose, the Deportation Law, which led to the “Armenian genocide”, was enacted in May 1915 during the First World War. The “cleansing movement” that thus began targeted Armenians and non-Muslim and non-Turkish peoples such as Greeks and Jews, Assyrians (Nestorians, Syriacs, Chaldeans), and Kurdish Yazidis. Immigrant and refugee Turks and other Muslim peoples were settled in the lands evacuated by their expulsion and massacre. One-third of the population of the Ottoman Empire at the time was displaced. Kurds, Arabs, Lazs, Albanians, Gypsies, Circassians, Georgians, etc., were intermixed to prevent them from becoming a threat to the transformation of Asia Minor into a “Turkish homeland”.

Mustafa Kemal continued the “Turkist” program of the CUP, especially its most prominent leader, Talaat Pasha – but with a difference: Mustafa Kemal rejected the CUP’s expansionism towards Asia and followed a more realistic path. For Mustafa Kemal, as for the Committee of Union and Progress leaders, the last remaining piece of land at hand was Asia Minor, namely Anatolia. “There was no other geography where the Turkish State could make a homeland.” In fact, as soon as he set foot in the Black Sea coastal city of Samsun on May 19, 1919, to launch the “national struggle movement”, his first action was to continue the cleansing of the Greek Christian minority (Pontus Greeks) living in that region. The “B-Team” of the CUP formed the main body of the cadre on which the Republic of Turkey was based until its foundation and thereafter.

In 1923, with the exchange agreement signed with Greece, all 1,200,000 Orthodox Christians in Anatolia were deemed “Greeks” and forced to migrate to Greece, while 500,000 Muslims in Greece were deemed Turks and forced to migrate to Anatolia. Since the criterion used in the exchange was not race or language but religion, Christian Turks in Anatolia migrated to Greece. In contrast, Muslim Greeks and some other ethnic groups in Greece migrated to Anatolia. Thus, it was Mustafa Kemal who completed the project of demographic Turkification and the transformation of Asia Minor into a “Turkish homeland” initiated by the leadership of the CUP.

Article 88 of the Constitution adopted in 1924 declared that “everyone who is a citizen of the Republic of Turkey is a Turk without distinction of religion or race”, making nationality a social and political identity determined by law.

In these conditions and environments, I was raised as a “Turk”. All members of my family were de facto “Turks”. Family history was never discussed. Only after I was 50 years old did I have the presence of mind to question this issue. The result I came to was extraordinarily surprising: Our family had no “Turks”! But we were all “Turks” anyway. The paternal side of my father was probably Arab and/or Sudanese and my mother’s side was Kurdish and Greek. My paternal side of my mother was Bosniak, and her mother’s side was Abkhaz. I wondered why

there was no Armenian, and it turned out that there was one in an indirect way: When my paternal grandmother adopted a girl from Erzurum who had been put in an orphanage because she had lost her family when she was five years old because of the Armenian massacre in 1915, that gap was filled! (I discovered that this girl was Armenian by managing to enter the state’s civil registry records). In other words, there was “everyone” other than a Turk in my family! Yet we were all still “Turks” and “Muslims” despite everywhere in my childhood and youth; when I thought I was a “Turk”, I don’t remember ever feeling “happy” for this reason; there was no such atmosphere in the family anyway. From my youth onwards, in terms of my political preferences, I was already categorically against nationalism.

You are the grandson of Bedirkhan Bey. How and when did you learn that you are Kurdish and the grandson of Bedirkhan Bey? What effect did this have on your inner world? How did you feel? And what did you know about Bedirkhan Bey till then?

It all started with a letter I received from my sister Ekin (Kardam) Duru, dated December 24, 1992, and the enclosed notebook written in Arabic script and its typed transcription. According to my sister’s letter, our paternal grandmother, shortly before her death, sometime between 1974 and 1976, gave my sister the handwritten notebook she had sent in this envelope and said, “This notebook contains the biographies of our family elders, keep it safely”. My sister threw this notebook, which she could not read because it was written in Arabic script, into a box where she kept other documents and never looked at it again until 1992 when she wrote this letter. She took that notebook, which was written in Arabic script, out of the box and had it transcribed (converted into Latin letters), and now she was sending me both that notebook and the Latinized version of it as a New Year’s gift.

The notebook author was Ali Galip Pasha, my grandmother’s father. The mere act of touching these faded pages written 59 years ago (in 1933) by my grandmother’s father Ali Galip, who was already dead when I was born and about whom I knew nothing but his name, was exciting. But what excited me was learning something I never knew about my family history: Ali Galip Pasha was a descendant of Mihal Kosses [Michael Kosses], a Byzantine tekfur (local Byzantine governor) who had collaborated with the Turks in the establishment of the Ottoman Principality, the first nucleus of the Ottoman Empire; in other words, he was Greek. As if that wasn’t enough, in 1882, he married Sariye, the daughter of Necib Bey, the second eldest son of the Kurdish Bedirkhan Bey. In other words, my grandmother was Greek on her father’s side and Kurdish on her mother’s side!

I vaguely knew who Michael Kosses, Köse Mihal in Turkish, was from my high school history classes, but I knew nothing about Bedirkhan Bey except that he was a Kurdish bey. My grandmother, father and uncle were no longer alive; I could not ask them. My mother was still alive, but she knew nothing about her mother-in-law’s (my grandmother’s) father or mother. She didn’t even know that her husband was Kurdish; she found out from me! My older sister Ekin and my cousin Nükhet, who are still alive, heard that we were somehow related to a Kurdish bey named Bedirkhan, but that was all. They had no idea who Bedirhan Bey was, how we were related to him – they had no idea.

That’s when I realized that, ever since I could remember, nothing was ever talked about my grandmother’s father and mother in the family. My grandmother rarely mentioned that her father’s name was Ali Galip and that he was a pasha of Sultan Abdülhamid the Second – that was all. After the military coup of March 12, 1971, I had to leave Turkey because the police were after me. I spent my last day in Istanbul with my grandmother. That night she talked about the Hamidiye Regiments, the Kurdish regiments formed by Sultan Abdülhamid. Her eyes were shining as she spoke. But my mind was on the dangerous journey I would make the next day; moreover, I was completely unaware of what the Hamidiye Regiments were. I couldn’t ask her anything, so she cut it short. If I had asked, she might have told me everything about my father’s family history, which was kept secret till then. The next day we said goodbye, and that was the last time I saw her. My father’s name was Ali Galip. So he was named after his grandfather, but I never once heard him mention his grandfather’s name; likewise, his grandmother Sariye Hanim, who I now know was Kurdish and a Bedirkhanian, seemed to have never existed. There was something strange about this that I had to find out what it was! I had learned that my paternal grandmother was Bedirkhanian on her mother’s side, but what kind of kinship was this? And how was her grandfather Necib related to Bedirkhan Bey? Who was I?

However, it was only in 1989 that I was able to return to Turkey, which I had left immediately after the military coup of September 12, 1980; I had spent a year and a half in prison and had just regained my freedom in April 1991; my wife and I were trying to rebuild our life from scratch. I did not have the luxury of dealing with revealing family secrets.

The years flew by as we struggled to build a new life. Finally, in 1998, I told my Kurdish colleague at the publishing house where I had just started working about the notebook my sister had sent me six years earlier, saying that I was curious to know how I was related to the Bedirkhanians, but that I could not find a way to find out. He told me that his friend, a Kurdish historian living in Sweden, was researching the Bedirkhanians and suggested that I contact him, giving me his phone number. This Kurdish historian had authored Bedirkhanians of Cizira Botan, which had not yet been published in Turkey. I immediately picked up the phone. When he told me about this book published in Sweden and said, he could send me a copy, the entire world became mine.

Soon I had the book in my hands. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I looked at the “Genealogy of the Bedirhanians” in the second chapter and saw the family tree going back to my father and uncle: Necib Bey, the father-in-law of my paternal grandmother’s father Ali Galip Pasha, was the second eldest son of Bedirkhan Bey of Cizre-Botan. One of Necib Bey’s three daughters was Sariye hanim (lady). Ali Galip Pasha had married this Sariye hanim. She had three daughters from this marriage. One of these three daughters was my grandmother Nazire (Kardam). Accordingly, I was the fifth-generation descendant of Bedirkhan Bey!

It had become my greatest desire to be able to conduct research based on archival documents on Bedirkhan Bey, whose life and struggle I had learned the first detailed information about from this Kurdish historian’s book, and to unravel the mystery of the family’s silence about our relationship with the Bedirkhanians. But for this, I had to retire myself and devote all my time to this work. Only nine years later, at the end of 2007, I had the financial means to do so.

In 2008, I accessed the Ottoman Archives and found about eight hundred pages of archival documents on Bedirkhan Bey (1806-1869) in Arabic manuscripts. I spent a fortune to convert them into Latin letters and a lot of time to understand 19th century Ottoman Turkish and spent five years to write two volumes of books: The first volume is about Bedirkhan Bey’s 10-year resistance and rebellion against the Ottomans, and the second volume is about his 22-year exile.

As a result of this study, I think I was able to solve the mystery of the family’s silence about Bedirkhan Bey: My paternal grandmother’s uncle Abdürrezak, Bedirkhan Bey’s grandson, was a famous member of the family who rebelled against the Ottomans and fought for an independent Kurdistan. In 1906, he was sentenced to life imprisonment for allegedly having the mayor of Istanbul murdered. When he was pardoned in 1910, he defected to Russia and during the First World War, with the support of Tsarist Russia, he formed an armed Kurdish force that worked with the Russian army to secede from the Ottoman Empire and establish an independent Kurdistan. The Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) government secretly sent special assassins to Russia to capture or kill him. When Russia withdrew from the war after the Socialist Revolution of 1917, he was captured by Ottoman army officers in Tbilisi or persuaded to return and brought to Damascus in 1918, where he was poisoned to death. After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1927, when Mustafa Kemal mentioned the Bedirkhanians as a threat to the regime in his famous speech to the parliament, I concluded that my grandmother’s family (her parents, herself and her husband), out of concern to protect the next generations, decided to hide the family’s Bedirkhanian origins and raise them as “Turks”.

In this way, I was deeply moved and outraged that the paternal side of my family had to consent to the assimilation and Turkification of the new generations to the bone to protect them from Kurdish hostility. But most importantly, I had a profound enlightenment about the historical roots of Turkey’s lawlessness and lack of democracy and basic human rights.

What would you like to tell us about your great-grandfather Bedirkhan Bey?

Bedirkhan Bey inspired the later Kurdish national awakening and struggle with his resistance and rebellion against the revocation of the autonomy granted to Kurdistan by the Ottoman Sultan Selim in the 16th century and his alliance with numerous other Kurdish begs in the 1830s-1840s. Furthermore, during his ten-year rule from 1837 to 1847, he became legendary for his “fair” governance of the Cizre-Botan principality through the “consultative council” he established, for the economic prosperity he ensured and the fair tax policy he implemented, for his resistance to the interference of the Ottoman-appointed regional governors against him and his allies, for creating an unprecedented atmosphere of public order and security in the Cizre-Botan principality, and for his social solidarity practices. This legend is still fresh. On the other hand, unfortunately, there is also the “Nestorian massacre” in his record, which the Christian world has never forgotten, and which is still fresh in our memories, and this constitutes the darkest page of Bedirkhan Bey’s life.

The Assyrians went down in history as the Nestorians who lived in Hakkari. What do you know about the Nestorians?

What I know about the Nestorians –a branch of the Assyrians, one of the oldest inhabitants of Kurdistan– is limited to what I could learn while researching Bedirkhan Bey’s massacres against them. The Nestorians targeted by Bedirkhan Bey’s massacres lived in the villages along the Zap River in the Çukurca district of Hakkari, near the Iraqi border. Six Nestorian tribes lived in this region: Named after the places where they lived, these tribes were: Tiyari, Thuma, Cilo, Istazin, Baz and Diz.

The patriarchal center of the Nestorians was the village of Koçanıs in Hakkari (today’s Konak village). The patriarch, Mar Shamun, was elected at a joint meeting of the bishops and the tribal lords called “malik”. In the 1840s, the total population of Nestorians in the Hakkâri region was around a hundred thousand. Nestorians were included in the target of the Armenian genocide organized by the CUP in 1915, and thus the Hakkâri region was completely “cleansed” of Assyrians.

You clearly consider the Nestorian massacre committed by your great-grandfather Bedirkhan Bey as genocide. Could you explain this to us a little bit? What kind of events took place? Based on your research, how many Nestorians were massacred?

Bedirkhan Bey’s massacre of Nestorians took place in two phases, one in 1843 and the other in 1846. The first phase began in June 1843 and lasted until mid-August. The second phase began three years later, in the last days of September 1846, and ended in October. In both attacks, Bedirkhan Bey’s military strength was approximately 10,000. The number of Nestorians slaughtered in the first campaign was about 10,000, and twice that number in the second, about 20,000. According to Gabriele Yonan, the total Nestorian population in this region in the mid-19th century was around 100,000. If so, it seems that Bedirkhan Bey wiped out a third of the Nestorian population with these two massacre campaigns. This alone is enough to say that this massacre was a complete genocide by today’s criteria. In my opinion, however, it is not only the number of Nestorians killed that makes this event a “genocide”.

In 1843, the first massacre began with the movement of the first company of the Kurdish army prepared by Bedirkhan Bey to attack the Nestorians towards the Diz region. The ten thousand-strong Kurdish army included, in addition to Bedirkhan Bey’s troops, those of Nurullah, the Bey of Hakkâri, Ismail Bey of Amêdiye, the Otaşı clan and Tatarhan Agha. The military strength of the Nestorians was greater than that of the Kurds: 15 thousand. But there was no unity among the Nestorians. The reason for this was the reaction against the patriarch Mar Shamoun’s collaboration with the British and American missionaries and their activities to convert the Nestorians from their old beliefs. There was strong opposition to Mar Shamoun, especially among the Nestorians of the Thuma region – so much so that this region sided with the Kurds during the massacre. This “division” seems to have been the reason for the Nestorians’ defeat at the hands of Badirkhan Bey’s forces.

Kurdish forces reached the first target, Diz, on June 6, 1843. Although they encountered strong resistance as they crossed the Great Zap, the outnumbered Nestorians retreated. For three days, the Kurds inflicted heavy casualties on the Nestorians, without discriminating between children, the elderly, women, and men. Diz was the home of Patriarch Mar Shamoun, but he was in Ashita at the time of the attack and escaped the massacre. However, his mother and one of his brothers were killed, and his three brothers and sister were taken captive. The other two brothers escaped and saved their lives.

While this first Kurdish army unit attacking Diz waited for reinforcements from Bedirkhan Bey and Nurullah Bey, the captives were taken to the Botan mountains. While Bedirkhan Bey was advancing northwest of the Tiyari region from Botan, the governor of Mosul, Mehmed Pasha, deployed an Ottoman contingent of eight hundred men southwest of the Tiyari region. Despite a promise of assistance to the patriarch Mar Shamoun, this troop did not help the Nestorians, but instead stood by and watched the massacre as an act of threat and blackmail. Meanwhile, some Kurdish troops guarded the passes east of Tiyari to prevent any help or escape from the east. Thus, the Nestorians of Tiyari were surrounded by the forces of Badirkhan Bey from the north and Mehmed Pasha from the south so that they could not escape to the east. At around the same time, a Kurdish contingent from Revanduz began to move towards Tiyari to assist Bedirhan Bey and Nurullah Bey and to “fight for the sake of religion”.

Bedirhan Bey entered Tiyari from the north and his first target was the village of Chamba. Among those who survived the massacre and were taken prisoner was Melik Ismail’s wife. Melik was wounded by a cannonball during the battle and hid in a cave with a broken hip, but when the Kurds found him there and dragged him to Bedirhan Bey, he was killed with a sword blow by Bedirkhan Bey himself.

The next target after Chamba was Serspidion, just to the south. The village is razed to the ground, gardens and fields are destroyed. The Zap Stream is crossed, and the church of Mar Sava is set on fire; the large arch and walls are destroyed. Bedirhan Bey then marched south along the Zap Stream towards Ashita. In the village of Minyanish on the way, all but twelve families were massacred.

The Nestorians from Tiyari met Badirkhan Bey two hours ahead. After a battle between the two forces from morning to afternoon, the Nestorians retreated and destroyed the bridge as they crossed to the other side of the Zap. Bedirkhan Bey’s forces crossed the Zap on small rafts and fought with the fugitives for two days, eventually defeating the Nestorians. Those who could not escape from Ashita asked for mercy, promising to pay the poll tax and obey Nurullah, the governor of Hakkari. 50,000 kuruş was collected from them. All but one tower of the mission building built there by the American missionary Dr. Grant was demolished, and about three thousand sheep were confiscated. Bedirkhan Bey fed the sheep to his soldiers and built small rafts with their hides to take his troops across the Zap Water. As he left Ashita, he appointed an ally of his, Zeynel Bey, to govern Ashita with some soldiers. 870 rifles were captured in the fighting. Bedirhan Bey would later dismantle the stocks and lighters of these rifles and send the iron to the governor of Erzurum. The manuscript holy books that the Nestorians had hidden in the mountains or buried in safe places during the massacre were never found because most priests who had hidden them were killed.

When news of the massacre in Ashita spread throughout the Lisan valley, a thousand of the Lisan people, including children and women, tried to protect themselves by climbing to a high and almost inaccessible platform southwest of Ashita, which could only be climbed by mountain goats. Realizing that he could not force them down, Badirkhan Bey encircled them and waited. Running out of food and water, the Nestorians surrendered after three days. After being promised by Bedirkhan Bey that their lives would be spared, they agreed to surrender their weapons. The Kurdish forces, who were allowed to enter the platform, collected the weapons of the Nestorians and began to slaughter them all, and when they were tired, they threw the rest off the cliff.

On July 27, 1843, the patriarch Mar Shamoun, who had been in Ashita at the beginning of the massacre, arrived in Mosul with a brother and the Ashita priest Abraham and his family, where he sought refuge with Rassam, the British vice-consul in Mosul, and asked the governor of Mosul, Mehmed Pasha, to help release the captives taken by Badirkhan Bey for sale, return the looted goods and property, and stop the ongoing massacre. Governor Mehmed Pasha stipulated that Mar Shamoun and all Nestorians must first swear allegiance to him to help the Nestorians, but Mar Shamoun refused. Moreover, since the Kurdish forces that carried out the massacre were in the entourage of the governor of Erzurum, it was beyond his authority to intervene in the massacre. The British consulate in Mosul also requested the return of the prisoners from the governor of Mosul. However, the response he received was that “there was no order from the state on this matter”.

The massacre lasted until mid-August 1843. Those Nestorians who managed to escape fled in droves to Mosul in the south. But if their route took them through Berwari, they were killed on the orders of its governor (and uncle of Zeynel Bey, who had been appointed administrator of Ashita) Abdulsamet Bey.

In November 1843, the Nestorians of Ashita revolted against the tyrannical rule of Zeynel Bey, who had been left in charge of them. One morning, at dawn, they attacked the partially demolished missionary building where Zeynel Bey and his men were staying, taking twenty of Zeynel Bey’s men hostage and killing five of them. Zeynel Bey and the rest of his men were trapped in the ruined building without food or water. Bedirhan Bey then sent troops to Ashita again and had around 500-600 people massacred.

Apart from the Thuma region, which he left untouched because they cooperated with him, the toll of Bedirkhan Bey’s massacres in Diz and Tiyari was very heavy. According to Gabriele Yonan, not even during Timur’s Mongol raids was such a horrific massacre; one fifth of the total Nestorian population of Tiyari was slaughtered.

According to Austen Henry Layard, the death toll of the massacre was 10,000. Many women and children were taken captive, some were sold in slave markets, others were given as gifts to favored Muslims. Among the Nestorians who escaped with their lives and crowded into Mosul, a typhus epidemic broke out and many of them died of it. Among those who died of typhus was Dr. Ashael Grant, an American missionary who had opened his house in Mosul to Nestorian refugees (April 25, 1844).

Three years later, in 1846, Bedirhan Bey launched a second massacre of Nestorians. After the first massacre, all missionary activity among the Nestorians had ceased. Even the Patriarch Mar Shamoun could not go to the region and fulfill his spiritual functions. During the first massacre, Mar Shamoun and the missionaries were the main sources of all news about the disaster. Since this source is no longer available, the only source for the details of this second massacre is Austen Henry Layard, who was conducting archaeological excavations in the ruins of Nineveh. In late August 1846, Layard traveled to the region and learned that the Nestorians of Thuma, who had been glad to be spared the massacre of three years earlier, were now in great anxiety and that Bedirkhan Bey was preparing an attack against them by the end of Ramadan. While the women were busy burying their jewelry and utensils in safe places, the men were busy preparing their weapons and making gunpowder. The Nestorians in the Baz region also began hiding their church books and belongings. Since the road to Mosul is under Kurdish rule and control, they were cut off from the outside world.

One day right after Ramadan, between September 23-26, 1846, Badirkhan Bey attacked Thuma with 10,000 men through the Tiyari mountains. Along the way, he plundered and extorted tribes. Thuma fought under the leadership of the Maliks and resisted for a while but was defeated to numerical superiority. Another massacre is committed without discrimination. Some three hundred women and children were slaughtered as they tried to flee to Baz. The most beautiful villages and their gardens were burned to the ground, and churches were razed. Almost half of the population was killed. Among them was the priest Kasha Bodaka, the melik, and the most learned of the Nestorian clergy, Kasha Oraha and Kasha Kana. After Bedirkhan Bey withdrew from Thuma, the few villagers who had somehow survived returned to their devastated villages, only to be attacked by Nurullah Bey, who thought they knew where the hidden money and gold were. Many died under torture; others fled to Iran as soon as they were freed. Layard says, “This is how this beautiful land is destroyed.”

According to the French consulate in Mosul, “Bedirkhan Bey massacred more than 20,000 people, men, women and children.

In the short term, the Nestorian massacre gave Badirkhan Bey an important advantage over the Ottomans. The “success” he achieved with this attack gave him a greater prestige in Kurdistan, more than even he had expected, and reinforced and consolidated his authority over other Kurdish begs and the ulema. His fame spread beyond the Ottoman borders. His crushing and subjugation of the Nestorians, who had been unable to be subjugated by the Ottomans for centuries and who were an important power center in their region, increased his influence, especially in Iran. However, these were not lasting gains, and they did not lead to the success of the ongoing struggle for autonomy. On the contrary, the first massacre in 1843, followed by the second massacre in the fall of 1846, became the decisive factor in his defeat in 1847. After both the first and the second massacres, the heavy pressure exerted by Britain and France on the Ottoman Empire for the immediate liquidation of Bedirkhan Bey forced the Ottoman government to undertake a military operation that it would not have otherwise been able to afford, and perhaps for a much longer time span. As a result of the Nestorian massacres, the Kurdish resistance led by Badirkhan Bey became a target for the entire Christian world. This gave the Ottoman administration the opportunity it had been looking for to crush the Kurdish movement.

What was the attitude of the Ottoman administration towards this genocide? Was it aware of the preparation of the genocide? Did the Ottoman administration take precautions, or was it in the attitude of “Let them eat each other’s heads”?

Yes, it was like you said.

Bedirkhan Bey did not inform the Ottoman administration about his first attack against the Nestorians and did not ask for any permission. As a matter of fact, he told Setevens, the British vice-consul in Samsun, who met him after the massacre, “I regret that I took this step without consulting my government. I did not know that European governments would come to the defense of these people”. But be that as it may, the Nestorian massacre was by no means unexpected for the Ottoman administration. The governors of Erzurum, Mosul and Diyarbekir had reported to the Grand Vizier at least three months before the massacre that Bedirkhan Bey was preparing for such an attack. In his report to Istanbul, the governor of Erzurum, while reporting that Bedirkhan Bey was preparing to attack the Nestorians, also stated that “it was not wrong that he was thinking of taming the Nestorians”. He merely stated that the timing of this attack was not good and suggested that it would be better to postpone it and that the Grand Vizier’s Office should send a letter to Bedirhan Bey to convince him to postpone his attack. But in case Bedirkhan Bey still attacked spite of such a letter, he advised that Bedirkhan Bey should not be treated harshly and that it should be tried to take advantage of him. However, the Grand Vizier’s Office neither disagreed with these views of the governor of Erzurum nor sent any “grand vizier’s warning” to Bedirhan Bey. Thus, by de facto supporting this policy proposed by the governor of Erzurum and by not warning Bedirkhan Bey, the Ottoman administration paved the way for the Nestorian massacre to the utmost.

The Ottoman administration, which had already decided to pursue a policy of harshness against Bedirkhan Bey, had no reason to feel uncomfortable with Bedirhan Bey’s unauthorized attack on the Nestorians. Such an attack would have given the Ottoman government another excuse to squeeze Bedirkhan Bey. At the same time, the Ottoman administration would have no objection to the oppression of the Nestorians by Bedirkhan Bey, who it believed were being provoked by the missionaries. It was also understandable that Bedirkhan Bey, aware of Istanbul’s discomfort with missionary activity in the region, did not need to ask the Grand Vizier’s permission for the attack. It was enough for Bedirkhan Bey that the governor of Erzurum encouraged him to carry out the attack. Bedirkhan Bey openly stated that he was “commissioned by the governor of Erzurum” for the Nestorian massacre, and he thought that the Ottomans would consider the massacre of Nestorians by him as a service to the state.

Since he probably organized his second attack to intimidate the Ottoman administration, which he had heard was preparing to attack him in the face of pressure from Britain and France, it would have been out of the question to inform the Grand Vizier and ask for permission.

In our telephone conversation, you mentioned your proposal to Kurdish organizations and leaders on the 170th anniversary of the Nestorian Genocide. Could you please elaborate on this proposal, why it was not realized, and do you still stand by this proposal?

June 2013 was the 170th anniversary of the Nestorian genocide. A few months before, at a meeting of the Advisory Board of the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), of which I was a member, I proposed an action that could be taken on this anniversary. I suggested that organizing a commemoration event with the slogan “Never Again!” in June 2013, in the region where the Nestorian massacre took place 170 years ago along the Zap Valley, could be a meaningful action that would make a big impact on an international scale. This proposal was not met with any objection, but no steps were taken in this regard either. I have no information as to why this proposal was not realized. I believe that commemorating this Assyrian genocide, which is now 180 years old, in one way or another, and saying “Never Again!” will never lose its relevance.

At that time, there was intense missionary activity among the Nestorians in Hakkâri. How did the Muslim Kurds react to this activity? Can it be said that these missionary activities played a role in the Nestorian genocide?

It can be said that the activities of the missionaries among the Nestorians in the late 1830s and the first half of the 1840s played a certain “role” in this genocide. But this role is limited to creating a pretext for the genocide and cannot be shown as an excuse to justify this crime against humanity. The perpetrators of the Nestorian massacre are Badikhan Bey and the Kurdish begs such as Nurullah of Hakkari, Ismail of Amediye and other Kurdish beys who encouraged and sided with him, as well as the Ottoman administration who stood by and watched this massacre, and the Ottoman governors of Erzurum and Mosul who encouraged Badirkhan Bey.

Until the late 1830s, no evidence exists that the relationship between the Nestorian tribes living in the Hakkari emirate and their Kurdish neighbors was hostile. Surma Hanim (Surma d Bayt Mar Shamoun), the sister of Mar Shamoun Bünyamin, who assumed this position after the death of the patriarch during the Nestorian massacre, has this to say about Nestorian-Kurdish relations before the massacre of 1843:

“Our relations with the Kurds were generally friendly. This is a fact recognized by everyone. Naturally, [some] conflicts and disagreements arose. But [in 1843] a purely local conflict turned into a major catastrophe.”

Like Surma Hanim, almost all scholars who had studied the subject state that the occasional disagreements between the Kurds and Nestorians before 1843 were not extraordinary, that in such cases, a council was formed, bringing together the leaders of both sides and that the dispute was usually resolved after lengthy negotiations. Two factors seem to have upset the centuries-old balance of power between the two peoples and “turned a purely local conflict into a major catastrophe”. One was that the Ottoman Empire, after its heavy defeat in the battle of Nizip against the Egyptian governor Mehmed Ali Pasha in 1939, made “centralization” its main concern, ending the autonomy enjoyed by the Kurdish begs in Kurdistan, including the Assyrians. The second factor was the activities of American and British missionaries among the Nestorians around the same time. The Nestorians living under the sovereignty of Kurdish beys became stronger thanks to their relations with the missionaries, which led the Kurdish beys to see the missionaries as a vanguard force threatening their power. Thus, the tense relations between the Kurdish beys and the Nestorians turned into a conflict, which allowed the Ottoman administration to march on both sides. We can briefly summarize how the intervention of the American missionary Dr. Asahel Grant and the British missionary Percy Badger in the relations between the Kurds and the Nestorians created the pretext for the Nestorian massacre as follows:

The American missionary Dr. Asahel Grant, who had organized a very effective mission in Urmia in 1836-1840, returned to Kurdistan in 1841 and, together with the Nestorian patriarch Mar Shamoun, began to visit Nestorian villages to establish a mission in the region. His deepening of his relations with Mar Shamoun, bypassing Nurullah Bey of Hakkari, and his taking sides with Mar Shamoun on Suleyman’s side in the power struggle between Nurullah Bey and his nephew Suleyman, strained their relations with the Kurdish bey Nurullah. Mar Shamoun promised Suleyman that if he would support the independence of the Nestorians, he would ensure that he would succeed Nurullah Bey as governor of Hakkâri. In response, Nurullah Bey imposed new tax obligations on the Nestorians. Mar Shamoun, with the support of both Nestorian tribal leaders and Dr. Grant, refused to pay this tax. Meanwhile, Dr. Grant was constructing a huge missionary building and school on a strategic hill overlooking Asheta, the largest town in Tiyari and the capital of the region, which Bedirkhan Bey, Nurullah Bey, and other Kurdish beys perceived as a fortified fortress to be used against them.

Around the same time (1842), Ismail Bey, the emir of Amediye, south of the Nestorian homeland, launched a rebellion against the Ottomans in alliance with Bedirkhan Bey. The patriarch Mar Shamoun, who had initially promised to support Ismail Bey in his rebellion, withdrew his support upon the warning of the governor of Mosul, and thus turned against Ismail Bey, his ally Badirkhan Bey and other Kurdish beys.

Again, at about the same time (1842), the Archdiocese of Canterbury in England sent the British missionary Percy Badger to Mosul to establish an Anglican mission there, working among the Nestorians. Britain was planning to establish its sphere of influence in the region through the Nestorians against the influence of France, which had organized itself among the Catholic Chaldeans, and Russia, which was neighboring Kurdistan. The Nestorians, who have not yet come under the protection of a European Christian state, are seen as the vanguard of British interests. Britain’s aim was to unite the Nestorians who had not converted to Catholicism and to establish a “new Eastern Nation” under the leadership of the patriarch Mar Shamoun. Badger’s first act was to visit Mar Shamoun and present him with a letter from the Metropolitan of Canterbury promising him the protection of England and a “new Eastern Nation” with Mar Shamoun at its head.

It was through the accumulation of such events that the local tension between Nurullah Bey and Mar Shamoun escalated from 1842 onwards and turned into a bomb ready to explode at any moment.

Finally, to this picture must be added the increasing disobedience of the Nestorians, encouraged by the activities of the missionaries and the assurances given by Britain, against Nurullah, the governor of Hakkâri, and their attacks on Muslim Kurdish villages.

Most notably, Nurullah Bey himself and the Kurdish alliance led by Bedirhan Bey and the Ottoman governor of Erzurum complained that the Nestorians had long refused to pay taxes, looted some Muslim villages, burned and destroyed villages, turned mosques into churches at the instigation of Dr. Grant, and killed 16 Muslims who were descendants of the prophet of Islam, and that these actions were “intolerable”. Dr. Grant, in one of his letters to the Missionary Herald, wrote that the Nestorians in the Diz region had twice carried out large-scale attacks on their Kurdish neighbors from Julamerk.

To sum up, these were the pretexts for the massacre organized by the Kurdish beys against the Nestorians.

Bedirkhan Bey belonged to the Naqshbandi sect, and the people and tribes around him wanted him to “destroy the giaour (infidels)”. Do you think religion was a factor in this genocide?

Let me try to answer this question separately, first with respect to Bedirkhan Bey and second with respect to his entourage.

By the 1840s, central northern Kurdistan, Bedirkhan Bey’s sphere of influence, had come under the influence of the Naqshbandi order. As you have mentioned, Bedirkhan Bey, a very religious man, was a devout follower of this sect. However, I have not found evidence that Bedirkhan Bey, due to his deep Sunni-Shafiite beliefs, was hostile towards Christians or Jews simply because of their religious identity. But the same cannot be said for his behavior towards Yazidis. It is a fact that not only Bedirkhan Bey, but almost all the Muslim Kurdish beys and regional governors of the Ottoman Empire who were neighbors of the Yazidis had a special hatred towards them and often attacked them. Whatever their material basis, the moral justification for these attacks was that the Yazidis, although Kurdish, had a religious belief outside the three major Abrahamic religions, which they considered “satanism”.

One of the most obvious proofs that Bedirhan Bey harbored no animosity towards Christians was that his advisors and army commanders included Armenians such as Stephan Manoglyan, Oganes Chalkardan, Mir Marto and Mirzo. And his goldsmith was also an Armenian named Thomas Anton.

Furthermore, we know that during the Muslim attempts to massacre Christians in Heraklion, Crete, where he was sent as an exile after his defeat by the Ottoman army, he defended Christians with about 30 of his relatives and men and took some of them under protection in his own house, and that he fought to prevent the hanging of a Christian youth who was sentenced to death for allegedly killing a Muslim in Chania, Crete.

However, the same cannot be said for his entourage. He was surrounded by such zealous Naqshi clerics, especially Abdulkuddûs, his sheikhulislam. In his testimony after the defeat in 1847, Thomas Anton, Bedirkhan Bey’s Armenian goldsmith, referred to Abdulkuddûs, the mufti, and Zeynel Bey, who had been appointed administrator of Ashita after the first Nestorian massacre, as “bitter enemies of the Christians”. Mullah Mustafa, a member of Badirkhan Bey’s advisory council, was “a person who was disgusted to even see a Christian”. The powerful circle of clerics around Bedirkhan Bey, Nurullah Bey, and other Kurdish beys called for jihad against the Nestorian attacks on Muslims and seyids, saying that such a war would be regarded as “a good deed in the sight of Allah”.

In Turkish and Kurdish historiography, especially when it comes to Christian peoples, extra meanings are attached to the issue of “missionaries”. Why are the “national democratic demands” of these Christian peoples always dealt with in the context of “missionary provocation”?

It would be unfair to say that all Turkish and Kurdish historians, without exception, “attach extra meanings to the issue of missionaries”. Of course, some historians do so. Statist and nationalist historians who do so treat not only the Christian demands but all kinds of demands for “national-democratic rights” in the context of “provocation by enemies of Turkey/Islam”. When this demand concerns Christians, the instigators are “missionaries”; in other cases, the instigators are “Armenians/Greeks/Communists/etc.”. This standard pattern is used by reactionaries, chauvinist nationalists, and racists who accuse all forms of opposition as “separatism.”

Is it understandable that Assyrian and Nestorian Christians, who have been placed in the “opposing” camp since the emergence of Islam, who have been denied equal rights and conditions by religion, and who have been subjected to constant oppression and persecution, pin their hopes on foreign powers – missionaries – and expect support from them?

In my opinion, the legitimacy of the struggle of a people living under oppression and persecution for national-democratic rights, equal rights, and freedoms cannot be debated. How this struggle will be carried out, how it will succeed, with whom it will be allied, and from whom support will be expected are not issues related to the legitimacy of the struggle. Still, to the strategy and tactics to be followed, and there is no such thing as whether this is “understandable” or not, “justified” or “unjustified”. One can only speak of its rightness or wrongness, which is determined by the success or failure of that struggle.

As the grandson of Bedirkhan Bey, do you condemn the genocide your great-grandfather committed against the Assyrians?

I don’t think “condemnation” is appropriate in this context. I believe that there is no justification whatsoever for what Bedirhan Bey did. If I had the slightest doubt about this, I would not have called his action “genocide.” I feel great pain every time I mention this issue, whether in writing or orally. I feel the same pain every time I think about it. But this pain does not prevent me from openly confronting it, that is, writing about it, documenting it, recording it as much as I can.

There is a deep conservatism, even bigotry, in Turkish and Kurdish intellectual circles about the genocide. What would you like to say about the participation of Kurds in the genocide in general (both in the Bedirkhan period and the 1915 genocide)? How do you evaluate the fact that it is not only the state that denies it, but also the Kurds, who are part of those who carried out this genocide, have the same discourse of denial?

First, I would like to state that I do not find your judgment that “Kurds were part of the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide” and that Kurdish intellectuals “deny this genocide with deep conservatism, even fanaticism” to be correct. But let me leave this aspect of the issue for later and first try to address the issue of “Kurdish participation in both Bedirkhan Bey’s Nestorian massacre and the 1915 Armenian genocide”.

In answering an earlier question, I mentioned that the number of Kurdish troops that participated in the Nestorian massacres in both 1843 and 1846, carried out by Bedirkhan Bey and other allied Kurdish begs, was approximately 10,000 each time. It is known that this military force was composed entirely of Kurds. However, I have not been able to determine how much of this force consisted of Bedirkhan Bey’s soldiers and how much of it consisted of the soldiers of other beys. However, it is certain that the overwhelming majority of them were Bedirkhan Bey’s soldiers. The military forces of the Kurdish principalities were mainly composed of the members of the tribes (tribal troops) belonging to that principality. However, Bedirkhan Bey did not form his military force from tribal troops led by the chiefs of the tribes affiliated to him, but he formed elite units composed of the best soldiers of each tribe and under his direct command. In other words, Bedirkhan Bey had created a special, permanent, relatively “modern army” belonging to the emirate. In 1843 and 1846, we can assume that this “modern army” of Bedirkhan Bey constituted the main Kurdish force that carried out the Nestorian massacres. Bedirkhan Bey planned, ordered, and carried out the Nestorian massacre using this military force of about 10 thousand. His advisory council and other Kurdish beys encouraged him to carry out this massacre, not the “Kurds”. The “10,000 Kurds” who carried out this massacre are not “part” of Badirkhan Bey and his allies who “carried out” this massacre.

As for the Armenian-Assyrian genocide of 1915-16… We do not know how many people were involved in the massacre of the approximately one million people who lost their lives during the year and a half of this catastrophe. However, the claim that “the Kurds carried out the Armenian genocide”, i.e. that one million Armenians were massacred by the Kurds, which was propagated by the state, is not true even in numerical terms. The number of Christians taken out of Kurdistan on that death journey called “deportation” is only around 300 thousand. Since the total number of Christians who lost their lives during the genocide was around one million, two thirds of the victims (i.e., the majority) lost their lives outside Kurdistan, in the geography of the empire where Kurds did not live.

Moreover, according to this calculation, can it be said that “Kurds were part of the Committee of Union and Progress leadership that carried out this massacre” based on the fact that 300,000 Armenians were massacred in Kurdistan? We can also ask the question differently: Since the Jewish genocide during the Second World War took place in Germany, and the Nazis who carried it out were Germans, can it be said that “Germans were part of those who carried out this genocide”?

The government of the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), which carried out the Armenian genocide in 1915, of course, included some sections of the Kurds in the parts of this massacre that took place in Kurdistan. It is interesting to note the similarity between the reasons for its success and the reasons for the Nestorian massacre of Bedirkhan Bey and his allied Kurdish begs. In the 1840s, just as the balance of power that made peaceful relations between Kurds and Nestorians possible was disrupted by the interventions of the great powers through missionary activities, the balance of power that made peaceful relations between Armenians and Kurds possible was similarly disrupted in the run-up to the First World War. On July 13, 1878, the Ottoman state signed the Treaty of Berlin with Russia, Great Britain, Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, and Italy, and for the first time the “Armenian question” was included in an international legal and political text. This treaty is considered the “starting point of the problem”. With the Treaty of Berlin, the Kurds were excluded, and the door was opened for the Armenians to establish an “Armenian State”, including a portion of the geography of Kurdistan. Thus, the Kurds began to take a stance against the Armenians and all Christians living in the Ottoman Empire and against the European states that were the “protectors of the Armenians”. Armenian nationalist organizations, relying on this international support, became aggressive against the Kurds. On the one hand, this situation gave the government of the Committee of Union and Progress a vital opportunity to cleanse Anatolia of non-Muslim and non-Turkish peoples, primarily Armenians, and on the other hand, it was the prelude to a great catastrophe for both Kurds and Armenians. Before and during the 1915 genocide, Armenians and Kurds took up arms along the Russian border and inflicted heavy casualties on each other. I would like to share an interesting testimony about these mutual massacres between Armenians and Kurds. In his memoirs, Rafael Nagoles, a Venezuelan citizen who commanded the artillery unit in Van with the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Ottoman Army during the First World War, states that both sides suffered great losses in these conflicts between Kurds and Armenians and gives the following detail: “Kurds were killing Armenian men. The Armenian partisans, on the other hand, indiscriminately killed Kurdish men, women, and children.”

In 1891, the Ottoman Sultan Abdülhamid II began organizing the Hamidiye regiments. These were well-armed, irregular units composed mainly of Kurds under the command of tribal chiefs. In addition to Kurds, there were also regiments composed of Turks, Circassians, Turkmen, Yoruks, and Arabs. These operated in the Kurdistan territories of the empire. After the overthrow of Sultan Abdülhamid II in 1908 and the establishment of the dictatorship of the Committee of Union and Progress from 1913, the Hamidiye Regiments continued to function in the same way.

The Committee of Union and Progress tried to use the Hamidiye Regiments against Armenians in the genocide that began in 1915. These regiments were directly subordinated to the General Staff and were part of the army’s chain of command hierarchy. One of the sources of Kurdish participation in the 1915-16 Armenian genocide was these regiments, headed by Kurdish tribal chiefs. However, it should immediately be added that some of the tribal chiefs at the head of these regiments did not consent to using themselves and their tribes in the massacres of Armenians. For example, Kör Hüseyin Pasha of Heyderan, whose headquarters were in Patnos, was one of them.

One of the sources of Kurdish participation in the Armenian massacre was the sheikhs who were religious leaders. Those who were hostile to the Armenians had no difficulty in mobilizing the affected Kurds in line with instructions from the state. However, in addition to those who encouraged participation in the Armenian massacre, there were also many sheikhs who opposed it. For example, Sheikh Ubeydullah, the leader of the Kurdish uprising, openly opposed the suggestions of pro-Sultan Abdulhamid sheikhs to kill Christians and refused to allow the Armenians to be touched, issuing a fatwa on the eve of the First World War that the killing of Armenians would be against both Islam and humanity. Sheikh Said Nursi, who fought against the Russian army in the Muş region, saved 1,500 Armenians from massacre and handed them over to the Russians. In addition, Sheikh Fetullah of Mardin also opposed the Armenian genocide. Another example is Mullah Selim. He met with the leaders of the Armenian Dashnak Party. He suggested that they should revolt together, arguing for a large autonomy and the joint administration of the common lands of Armenians and Kurds by these two nations.

Apart from these, there are so many testimonies of Kurds who opened their doors to Armenians who managed to survive the massacre and took them under their protection or who took care of Armenian children whose parents had been massacred. In this regard, the support provided to Armenians by the Kurds of Dersim should be especially mentioned.

The power that carried out the Armenian genocide of 1915 was the Ottoman state under the dictatorship of the Committee of Union and Progress. The Kurds have never been a part of this power or of the massacre it carried out in any way, even those whom the state managed to include in the massacre in different places and at different rates. The Kurds do not have any organization to make them a part of this massacre. Let alone being a part of it, they were in a way the victims of another massacre. I would like to take this opportunity to briefly summarize another great deportation that Kurds were subjected to around the same time, but which is widely unknown.

While the Armenian genocide was going on, the Kurds were subjected to another genocide of almost equal gravity. While deporting non-Muslim elements, the Committee of Union and Progress also deported Muslim Kurds in large masses from Kurdistan to western Anatolia to Turkify them, and forcibly settled them in the places they were sent to, never to return. The instruction dated May 2, 1916, sent by the Minister of Interior Talaat Pasha to the Governorate of Diyarbekir on this matter can be considered as the beginning of this practice. Data compiled in large numbers from various sources reveal that at least one million people from the Kurdish provinces, with a population of 1.5 million, were forced to become refugees, and more than half of this number died or disappeared due to various epidemics and migration conditions. Very few of the approximately 300,000 refugees who survived, almost all of them Kurds, could return to Kurdistan. Those who could not return were uprooted and disappeared. This is another genocide that took place in the same period but is little known.

As for the denial of the Armenian genocide… Calling the “events of 1915-16” a “massacre” or “genocide” has been a big taboo in Turkey almost until the early 2000s. Even today, it would not be wrong to say that the attitude of denial of this phenomenon is quite widespread, especially among Turkish intellectuals. But since the 2000s, many Turkish and Kurdish intellectuals have been engaged in a profoundly serious struggle to break this taboo, risking their own freedoms, and paying the price. Therefore, it would be grossly unfair to say or imply that all Turkish intellectuals, and especially Kurds, have a denialist discourse or attitude towards the “Armenian genocide”. All the parties of the Kurdish political movement – as far as I know – call what happened in 1915 a “genocide” in a truly clear and unambiguous way, and they support and share the Armenian demands for the state to recognize this massacre as “genocide” and on other issues. I can give too many examples to fit here. But the most striking example is the funeral ceremony held on January 23, 2007, after Hrant Dink, an Armenian who was the founder, editor-in-chief and chief writer of the Agos newspaper, was assassinated in Istanbul on January 19, 2007, after receiving threats for his views that he defended “in his Armenian identity” and which the state deemed “dangerous for national unity, solidarity and values”. Approximately 100,000 people, both Turkish and Kurdish, attended the ceremony in front of the Agos newspaper and chanted “We are all Hrant, we are all Armenians” for hours. Afterwards, the same protests with the same slogans were repeated in other major cities, including Malatya, his birthplace.

Another example is the widespread demand for “confronting our dark past” in the events leading up to April 24, 2015, the centennial of the Armenian genocide. For example, in the Kurdish city of Diyarbekir, the capital of Turkish Kurdistan, a conference titled “Armenians of Diyarbakir on the Anniversary of the Armenian Genocide” was hosted by the city’s bar association and organized with the contributions of the city municipality, which is run by the mainstream Kurdish political movement, and attended by Ara Sarafian, the director of the Gomidas Institute, editor of the Blue Book and historian and writer. Speaking at this conference, Tahir Elçi, the president of the Diyarbakir Bar Association and a Kurd, said the following:

“The persecution of the Armenian people and the official policies and practices were also shared by a section of the society, especially by the Kurdish tribal chiefs. The ‘Armenian truth’ is a key issue in confronting the past. Of course, official history and ideology deny this shameful crime committed against the Armenian community and therefore conceal the evidence of the crime. However, the Kurdish community, which has been struggling for their rights and order of law under tough conditions for decades, must help uncover the truth about the atrocities committed against their brotherly Armenian people.”

Seven months after he made this speech, on November 28, 2015, Tahir Elçi became a victim of an “unsolved murder” in Diyarbakir.

But it should be noted that the struggle against denying the Armenian genocide still has a long way to go. In my opinion, the Kurds need to promote further confrontation with these tragic historical events of the past. But this confrontation is a necessity for the Armenians, too – both in terms of what happened then and what was done to the Kurds in Armenia in 1991 and afterward…Please allow me to give a detailed example to help me concretize my view that confrontation should not be limited to the Kurds but should be mutual.

In 1991, Armenia’s official army and volunteer units of Armenians from the United States attacked and captured Lachin, the capital of Red Kurdistan, in May, killing 15,000 Kurds. The captors renamed Kashatag and declared it “an ancient Armenian city”. In the following months, the countryside of Red Kurdistan was systematically cleansed of its Kurdish population and historical monuments. Two years later, in April 1993, Armenian forces attacked Kelbajar, the most prominent Kurdish town in the region. After intense bombardment, the city was captured. The 100,000 refugees of the town’s inhabitants were forced to flee to the Murov mountain, more than 3,000 meters high, to escape death. The International Red Cross organization reported that 15,000 civilians who escaped death died in the snow. As the Ottomans did to Armenian civilians in 1915, in 1993, Armenians bombed Kurdish refugees, attacked rescue and evacuation vehicles, ambushed, and killed ordinary civilians. Kelbajar was razed to the ground, and its Kurdish name changed to Karvajar. In the following months, the destruction expanded to include the natural environment. The pristine forests around Kelbajar were logged and sold to the Armenian population for firewood. Kurdish identity and culture in Armenia are now facing extinction. Serj Sarkisyan, who carried out this genocidal massacre, later became Armenian President and was honored with the National Hero Medal and Vazgen Sarkisyan.

Confrontation does not mean looking at past events as a vendetta and apologizing to each other. In any case, an apology will not make anything that happened in the past as if it has not happened. Confronting is to reflect accurately and objectively what happened in history, free from prejudices and political calculations. Facing history does not mean forgetting what has been done. It is already impossible to forget the facts embedded in social memory. What matters is ensuring that the same things do not happen again as much as possible.

Would you like to send a message to the tens of thousands of Assyrians born in Chicago, Arizona, and some states in Australia and to other Assyrians living on other continents who know themselves as Hakkarians?

What I can humbly say to my dear Assyrian brothers and sisters is this:

I wish you could ask my great-grandfather Bedirkhan Bey directly to account for the massacre he committed against your ancestors! I guess it is up to me, before anyone else, to account for this genocide committed by Bedirkhan Bey. I tried to make this confrontation 12 years ago in the book I wrote on Bedirkhan Bey. Just like now, I repeat this confrontation at every opportunity I get; I don’t know how much I have succeeded; you are the ones who will appreciate it.

Dear Mr. Sabri Atman sent me the above questions in an e-mail message, in which he said:

Rest assured, there are thousands of people whose parents and themselves were born in Chicago, but when asked, “Where are you from” they will say, “I am from Hakkari.” Two names are engraved in their memory: The first is “Hakkari” and the second is “Badirkhan Bey.” This is how this situation is passed down from generation to generation. However, if you were to ask them to show you where Hakkâri is on the world map, most of them would not be able to do so.

You cannot imagine how these lines hurt my heart and soul! It was with these feelings that I tried to answer the above questions that were sent to me.

Please let us not forget the following: Members of any nation or people are neither entirely “good” nor entirely “bad”. The actions of one person or group, or social segment cannot and should not be attributed to the nation or people to which they belong.

Today, Turkey still struggles with the problems of a hundred years ago. Unless we confront those problems, we will not be able to have a democratic state of law that respects human rights. Unfortunately, there are no more Greeks, Armenians, Assyrians, or other ancient peoples and communities in these lands. But some Kurds have been oppressed, massacred, exiled, and assimilated to the same extent, if not more. They resist; they cannot be exterminated; they struggle for rights, freedoms, and equality alongside other progressive and democratic forces in Turkey. Please support as much as you can this arduous effort to transform Turkey into a country where the most basic rights are won, where democracy, law, and equality prevail, and where people come to terms with their past and make peace with it. Do not remain silent in the face of the injustices Kurds are subjected to and the massacres they suffer. I am convinced that the fire that flames in all our hearts and which we bequeath to the next generations will be extinguished with the success of this struggle.