Could you provide our readers with some information on your academic

I am a forensic psychiatrist with a position at the Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong. I am also a writer and historian with an interest in the history of medicine, genocide and pre-history. My background is Jewish and my grandparents, on both sides of the family, had to flee Tsarist Russia to avoid persecution. Some relatives who stayed were later killed by the Nazis. I have done some work with Holocaust survivors and had an interest in fake Holocaust claims.

When did you initially learn of the Assyrian Genocide and what sparked your interest in writing about it?

I have had an Assyrian friend since the mid-1990’s and learned from her about the ongoing persecution of Christian communities in the Middle East and the Assyrian Genocide. My interest in writing about it arose from my studies on the role of doctors and human rights abuse when it became evident that Turkish doctors had played such a prominent role in the terrible events of World War 1.

What has been your interaction with Australia’s Assyrian community and how would you evaluate their work towards genocide recognition?

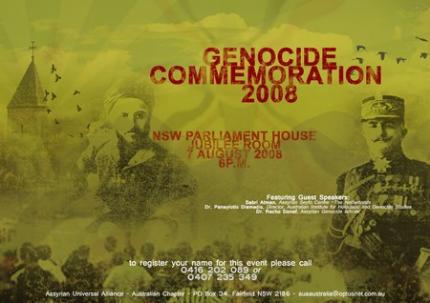

My involvement with the Sydney community has only started in the last two years. I have been impressed by their organisation, commitment and dedication to the cause. I have had the opportunity to give talks at seminars and interact with people on an informal basis. At present I am

trying to establish an on-line magazine (with the working title of Exunivir) to promote discussion and dialogue between all the groups who have suffered persecution in the Middle East (e.g. Assyrians, Armenians and Jews).

As your background is in psychiatry, what do you think the study of psychiatry within the scope of genocide can teach us about the nature of genocides throughout history?

Genocide involves social, historical, environmental, economic and psychological factors, among other things, and there is no doubt that an understanding of psychiatric issues can be of assistance. However, it is important not to make the assumption that perpetrators are automatically

dysfunctional, when in fact the majority are not.

From your inquiries into the historiography of the Assyrian genocide in the Ottoman Empire, do you see any distinct psychological trends or patterns of behaviour from amongst the perpetrators?

There is no consistent psychiatric disorder among such individuals. However, psychological studies, such as on the Nuremberg defendants, show that they tend to have a narrow focus, a rigid attitude with perfectionism and difficulty in changing their views.

What can the Assyrian genocide recognition movement learn from the Jewish community and its approach to remembering the Holocaust?

To be united and unswerving in their approach and response to ongoing abuses, as well as attempts at denial; to reach out and form links with other groups that have had similar experiences and losses; and, most important, to never forget and keep visible the memory of the victims .

What do you consider to be the rationale behind the intense nature of ongoing Turkish denialism?

The answer is in one word: Nationalism. The Turkish state, despite recent changes, remains completely wed to the nationalism of a century ago and completely unreconstructed in putting behind them the ideology that ordered and carried out the genocide.

In recent years, Assyrians have sought to pressure Turkey by gaining recognition of the genocide by countries around the world. Is this a sufficient approach? What more should Assyrians do to gain recognition and wider attention to the issue?

I believe that it a question of time before the Turkish state is brought to accepting the inevitable and recognising the genocide. It is however realistic to accept that this will not occur quickly and pressure must continue, otherwise the process will flag.

By Naramsin Daro