Adem Cetinay, collecting a petition against the memorial, with apparent sincerity says the memorial will create tensions where none previously existed, the logic of this statement being that it is better for the victims of the genocide to be left to choke on their despair, rather than have the temerity to disturb the world by commemorating their awful losses. By contrast, Julia Irwin, that well-known supporter of genocide victims, albeit those who happen to fall into the ambit of her political ideology, is curiously resistant to the idea.

What comes as a surprise to many is the personal intervention by the Foreign Minister, Stephen Smith, in a memo to the Mayor of Fairfield. Stating that "Australia does not intervene in the historical debate," he then resorts to the familiar weasel words employed by Turkish government lobbyists. This intervention by the Federal Government into what is essentially a matter of local government is curious, by any standards. Would they have had the same response to the unveiling of a monument to Raoul Wallenberg in Woollahra on the grounds that it would have upset the Soviet Government? Does this mean that the Cambodian, Rwandan and Sudanese communities are forever prohibited from commemorating their own tragedies on the spurious grounds that it will disturb community harmony? This is in marked contrast to the official attitude towards the vigorous — and rightly so — debate over the hotly disputed issue of the genocide of Tasmanian Aboriginals.

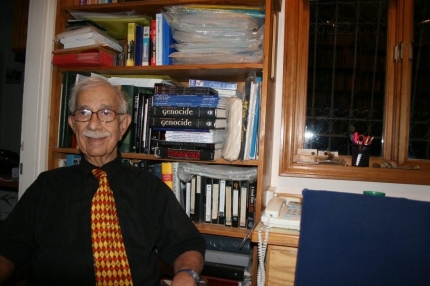

In short, the issue shows that nothing has changed and everything remains the same. Which brings us to the question of why this writer, a Jewish psychiatrist historian with ties to the Sydney Jewish Museum, is responding in this fashion.

Genocides are a fact of human history, but the 20th century, starting with the forgotten Herero genocide in German South West Africa, has distinguished itself in the most egregious and appalling fashion. The 1915 Genocide of Armenian and Assyrian people, in addition to the massacre of Pontine Greeks, by the forces of Turkish nationalism, provided a template for subsequent tragedies. While the events of the genocide do not require reiteration, several issues can be clarified. Thanks to the distinguished historian Vaclan Dadrian, we now know that leading figures of the Itihadist Movement who ran the genocide killing programme were physicians. The leading doctors were

Dr Behaeddin Sakir and Dr Mehmett Nazim, regarded as responsible for over a million deaths between them. The latter, in what must be regarded as one of the most misguided appointments in the history of medicine, was professor of Legal Medicine at Istanbul Medical School.

Many doctors were governors of the Eastern Anatolian provinces, playing a pivotal role in the establishment and deployment of the Special Organization units, extermination squads staffed by violent criminals. Furthermore, it was not a hands-off affair. Dr Mehmed Resid, involved in the ‘deportation’ of 120,000 Armenians, was extraordinarily brutal, his activities included smashing skulls, nailing red-hot horseshoes onto the victim’s chest and crucifying victims. Ophthalmologists gave eye drops to blind children. Other doctors, describing their victims as subhuman, used them as guinea pigs to infect with a range of diseases. Hundreds were injected with blood from typhus cases. Military pharmacist Mehmed Hasan was accused of murdering 2000 Armenian labour battalion soldiers and allowing his men to rape 250 women and children. Dr Ali Said killed thousands of infants, adults and pregnant women by administering poison as liquid medicine, and ordering drowning at sea of patients who refused the ‘medicine’. Dr Tevfik Rusdü killed his infant victims with a toxic gas, an ominous precursor of the gas chambers of Auschwitz and Treblinka.

The basis for medical involvement in the genocide was summed up in the statement of Dr Mehmed Resid before his suicide:

Even though I am a physician, I cannot ignore my nationhood. Armenian traitors… were dangerous microbes. Isn’t it the duty of a doctor to destroy these microbes? My Turkishness prevailed over my medical calling. Of course my conscience is bothering me, but I couldn’t see my country disappearing. As to historical responsibility, I couldn’t care less what historians of other nations write about me.

The attitude of the doctors who carried out the Armenian Genocide laid the template for the Holocaust. Furthermore, since World War II, involvement of doctors in state abuses has been something of a growth industry, showing that the medical profession, like the Bourbon Emperors of France, seems to remember everything and learn nothing.

The second issue on the Armenian and Assyrian Genocides is the official Turkish policy of denial. If you want to see the effects of denial of genocide, compare the situation in Germany and Austria. The latter, for political reasons, was designated the first victim of the Nazis, thereby avoiding post-war denazification or acceptance of the Holocaust. Recalling that Hitler was Austrian, it is worth noting that 1.2 million Austrians fought in the Nazi forces. Eichmann’s genocide staff was 80% Austrian; including three-quarters of concentration camp commandants. After the war, the Austrian state went to great lengths to foster the myth that most Austrians had opposed the Nazis. It took the Waldheim controversy to start a grudging process of recognition that Austrians occupied significant roles in the Nazi party, military, police and security apparatus, and had leading roles in organising the genocide.

The contrast with Germany (formerly the West German state) is notable. Its failings notwithstanding, the German government went to considerable lengths to educate its population and make it illegal to deny what had occurred. Not for nothing is Germany now the state with the fastest growing Jewish population in Europe — mostly from the former Soviet Union — while Austrian continues to tinker with far-right movements and make inept attempts to accept their role in the Holocaust.

Which brings us to Turkey, the only country in the world that has legislated, under the most severe penalties, the policy of genocide denial. Firstly, a government going to these extremes for such a lengthy period of time required the greatest of caution in any dealings.

Secondly, the sheer short-sightedness of the policy is obvious; if anything, it leads to more, not less, publicity about such issues.

The other reason to explain my involvement is a highly personal one. I am of course highly sensitised to the events of the Holocaust, which has a guiding influence on much of my writing. But there are many dedicated workers in the Jewish community to remember and investigate these events. The Christian communities of the Middle East, still denied closure of the 1915 genocide, attract my attention and whatever small assistance I can offer them. That they continue to be victimised in their ancient lands in what can only be regarded as an organised campaign to expel them, only adds to the situation.

The Assyrians, like the Armenian, Jewish, Chaldean and so many other communities, have formed part of the rich tapestry of the Middle East since the first agricultural settlements. Wherever they settle, they add immeasurably to the community well-being. More important, they bring with them that special diaspora quality of wit, warmth, wisdom and closeness that makes this a better place to be. This is certainly something to fight for.

By Robert M. Kaplan

Robert M Kaplan is a forensic psychiatrist, writer and historian at the Graduate School of Medicine, Wollongong University. His book “Medical Murder” was published by Allen & Unwin in June. He is currently writing about the Prophet Ezekiel and medical charisma.